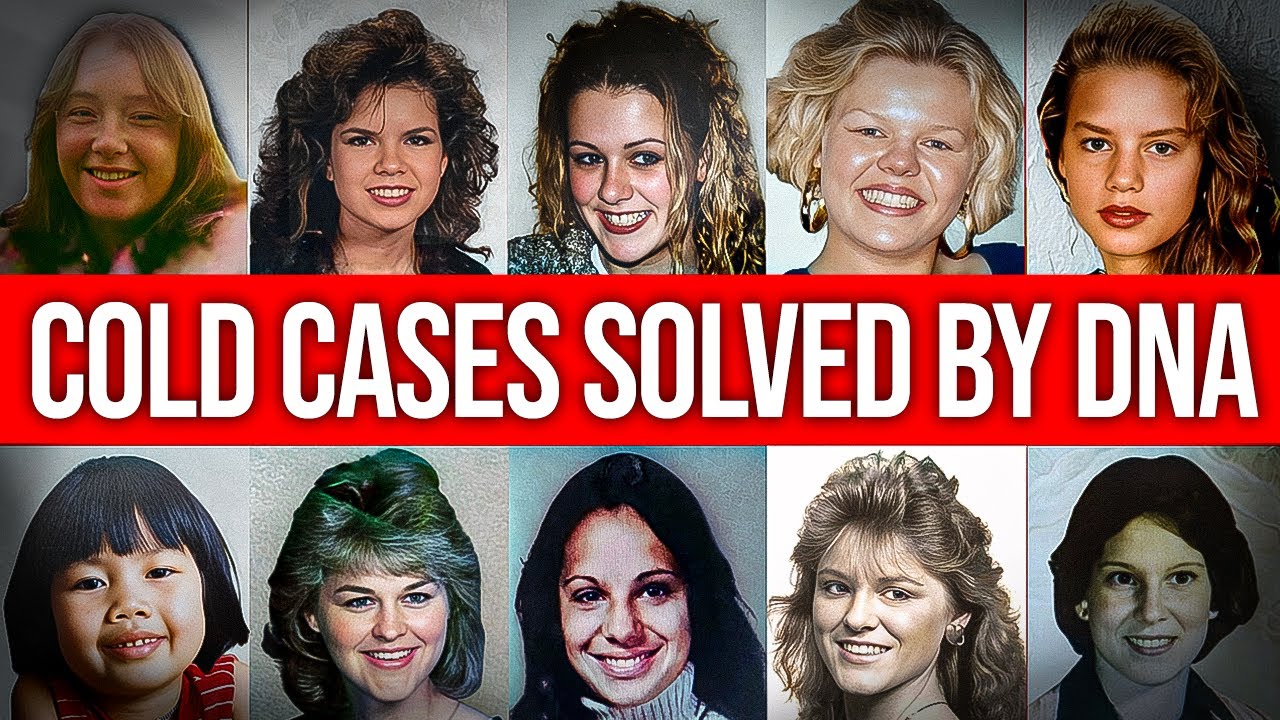

The passage of time is usually the enemy of justice. Memories fade, witnesses move away or pass on, and physical evidence degrades in dusty storage boxes. For the families of those who have been taken from them in violent, unresolved incidents, the years often bring a creeping despair that the truth will never be known. However, a quiet revolution has been taking place in the world of forensic science, one that has turned the concept of a “cold case” on its head. The emergence of forensic genetic genealogy has given a voice to the silent witnesses left behind at crime scenes—minute traces of biological material that can now speak across decades to identify perpetrators who believed they had gotten away with the unthinkable.

One of the most harrowing examples of this new era involves the case of Sherri Rasmussen, a tragedy that remained shrouded in mystery and institutional blindness for over two decades. In 1986, Sherri was a successful nursing director in Los Angeles, recently married and starting a new chapter of her life. She was found deceased in her home, the victim of a violent struggle. At the time, investigators quickly latched onto the theory that she had interrupted a burglary. It was a convenient explanation that fit the surface-level evidence, such as a stacked stereo that seemed ready to be stolen. However, Sherri’s family was adamant from the beginning that this was personal. They pointed to a woman named Stephanie Lazarus, a police officer and the former girlfriend of Sherri’s husband. Lazarus had reportedly been obsessive and unable to accept that her relationship was over.

Despite these pleas, the idea that a fellow officer could be responsible was dismissed by the authorities. The case went cold, and Lazarus continued her career in law enforcement, eventually rising to the rank of detective specializing in art theft. For twenty-three years, she wore the badge, walked the beat, and lived a life of perceived impunity. It wasn’t until 2009 that a cold case team decided to re-examine a bite mark found on Sherri’s arm. In the eighties, this evidence was of limited use, but in the twenty-first century, it was a goldmine. Saliva extracted from the wound yielded a DNA profile that didn’t match a random burglar; it matched Stephanie Lazarus. The shock within the LAPD was palpable. The arrest of one of their own exposed not just a singular act of violence but a systemic failure to listen to the victims’ families. Lazarus was convicted, proving that a badge offers no shelter from the truth of one’s own genetic code.

While the Rasmussen case highlighted the failure to catch the guilty, the case of Angie Dodge in Idaho Falls exposed the horror of punishing the innocent. In 1996, eighteen-year-old Angie was found deceased in her apartment. The pressure to solve the case led police to Christopher Tapp, a young man who was subjected to aggressive interrogation tactics. Despite the fact that his DNA did not match the biological evidence found at the scene, Tapp was coerced into a confession. He was sentenced to prison, where he would sit for twenty years, watching his youth evaporate for a crime he did not commit. Angie’s mother, Carol Dodge, was a relentless force. She refused to accept the official narrative when the science didn’t add up. She knew that the DNA left behind belonged to the real perpetrator, and she would not rest until that person was found.

It took until 2019 for genetic genealogy to finally untangle the web of errors. By uploading the unknown DNA profile to public genealogy databases, investigators built a family tree that pointed them to a man named Brian Lee Drips Sr. The revelation was sickening: Drips had been living across the street from Angie the entire time. He had watched the police investigations, the media frenzy, and the wrongful conviction of Christopher Tapp, all while living his life in freedom. Investigators confirmed his identity by collecting a discarded cigarette butt. When confronted, Drips confessed. His arrest led to the exoneration of Christopher Tapp, ending a nightmare that had lasted two decades. This case stands as a stark reminder that DNA doesn’t just catch the guilty; it is the most powerful tool we have for protecting the innocent.

The reach of this technology extends beyond single incidents to solve mysteries that have haunted entire regions. In the Pacific Northwest, the 1987 disappearance of Jay Cook and Tanya Van Cuylenborg was a dark cloud over the community. The young Canadian couple had traveled to Washington State for a simple errand and never returned. Their bodies were found in separate counties, victims of a brutal attack. For over thirty years, their families were left with nothing but questions. The investigation generated thousands of tips but no solid leads. The turning point came in 2018, shortly after the high-profile arrest of the Golden State Killer. Investigators applied the same genealogical techniques to the biological evidence preserved from the 1987 crime scenes.

The trail led to William Earl Talbott II, a truck driver who had no prior felony convictions and thus had never been in the standard criminal DNA databases. He had lived a quiet life, likely believing that his secret was safe after so much time had passed. Detectives surveilled him and retrieved a discarded cup to verify the match. Talbott became the first person ever convicted by a jury primarily based on genetic genealogy evidence. His trial and subsequent life sentence offered a long-overdue closure to two families who had aged without their children. It demonstrated that even those who have successfully evaded law enforcement for half a lifetime can be brought to account by the very biology they carry with them.

Sometimes, the truth is even more painful because of who the perpetrator turns out to be. The 1984 case of Christine Jessup in Ontario, Canada, is a heartbreaking example of betrayal. When the nine-year-old girl disappeared and was later found deceased, police zeroed in on Guy Paul Morin, a neighbor. Morin was wrongfully convicted and imprisoned, enduring a legal nightmare before DNA evidence exonerated him years later. But his release didn’t tell the police who did do it. The case remained cold for decades until 2020, when genetic genealogy identified the real culprit as Calvin Hoover. Hoover wasn’t a stranger; he was a family acquaintance who had been in the Jessup home, offering condolences and support to the grieving parents while harboring the secret of his actions.

The revelation was a double blow. The family had to process the fact that the man they had trusted was the one who had taken their daughter. Hoover had died by his own hand in 2015, five years before his identity was uncovered. While he could never be put on trial, the truth cleared the air of suspicion that had lingered over the community and fully vindicated Morin. It highlighted a terrifying reality: perpetrators are not always monsters hiding in the shadows; sometimes, they are the friendly faces we see every day.

These stories share a common thread of resilience—the resilience of families who refused to let their loved ones be forgotten and the resilience of biological evidence that outlasted the lies of those who tried to destroy it. The science of genetic genealogy has fundamentally changed the landscape of criminal justice. It sends a powerful message to anyone harboring a dark secret: time is no longer a shield. Whether it is a cigarette butt dropped in 1974, a letter licked in 1988, or a hair left behind in 1990, the truth is written in the cells, waiting for the right technology to read it. As we look at these resolved cases, we see not just the closing of files, but the healing of wounds that have been open for generations. The silence has finally been broken.

News

The 41-Minute Mystery: Why The Official Narrative on the Nancy Guthrie Case Just Shattered

The news broke on a quiet Saturday morning in Tucson, creating shockwaves that rippled all the way to the NBC…

Heartbreak in Port Charles: The Shocking Truth Behind Jane Elliot’s Final Exit and Why General Hospital Will Never Be the Same

The news hit the internet with the force of a tidal wave, leaving daytime drama fans across the nation absolutely…

General Hospital Shocker: Is This The End of The Road for Emma Scorpio-Drake? The Heartbreaking Twist That Has Fans Reeling

The air in Port Charles has been thick with tension lately, but nothing could have prepared General Hospital fans for…

General Hospital Stunner: The Queen of Fashion Wakes Up With the Perfect Clapback While Baby Daddy Drama Explodes in Port Charles

It is the moment every single General Hospital fan has been waiting for with bated breath, counting down the days…

he Billionaire’s Breeding Experiment: Inside the Desert Ranch Where Science Went Dark

It is the year 2006 in St. Thomas, and the room is filled with some of the most brilliant minds…

The Unthinkable Nightmare: Inside the Terrifying Disappearance of Savannah Guthrie’s Mother and the High-Stakes Federal Hunt for Answers

It happened in the blink of an eye, shattering the peace of a quiet Arizona evening and plunging one of…

End of content

No more pages to load