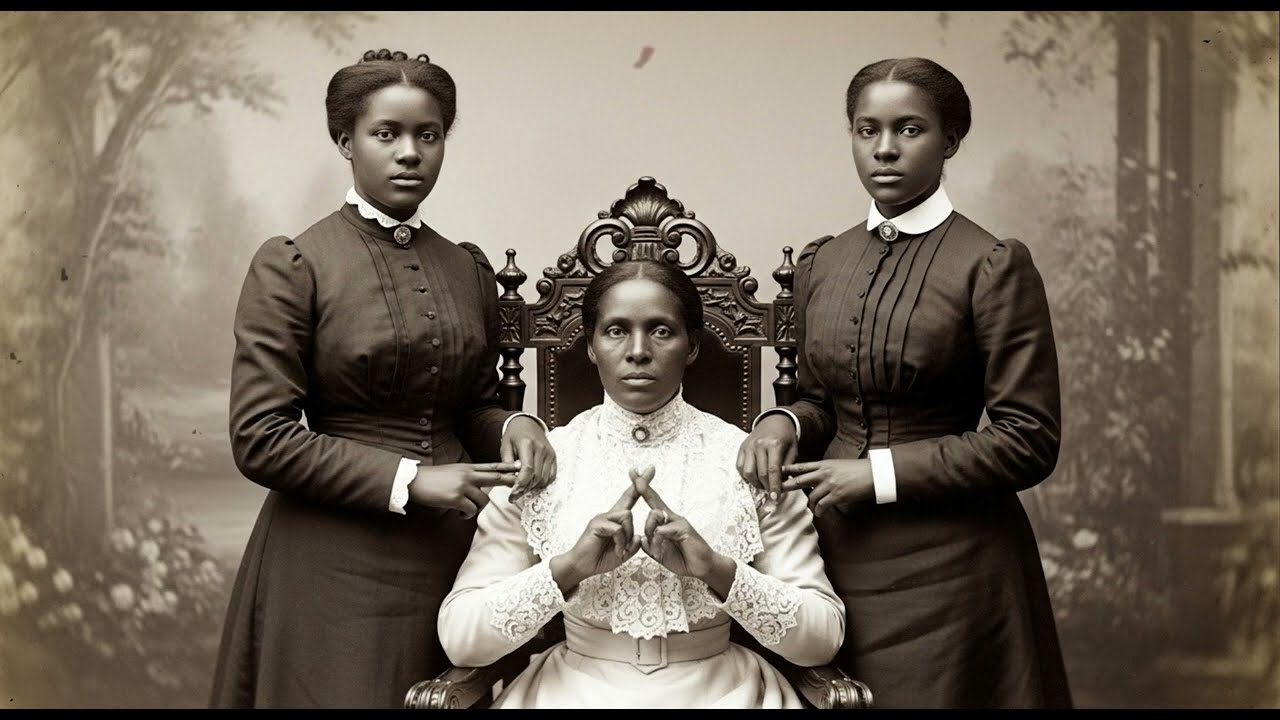

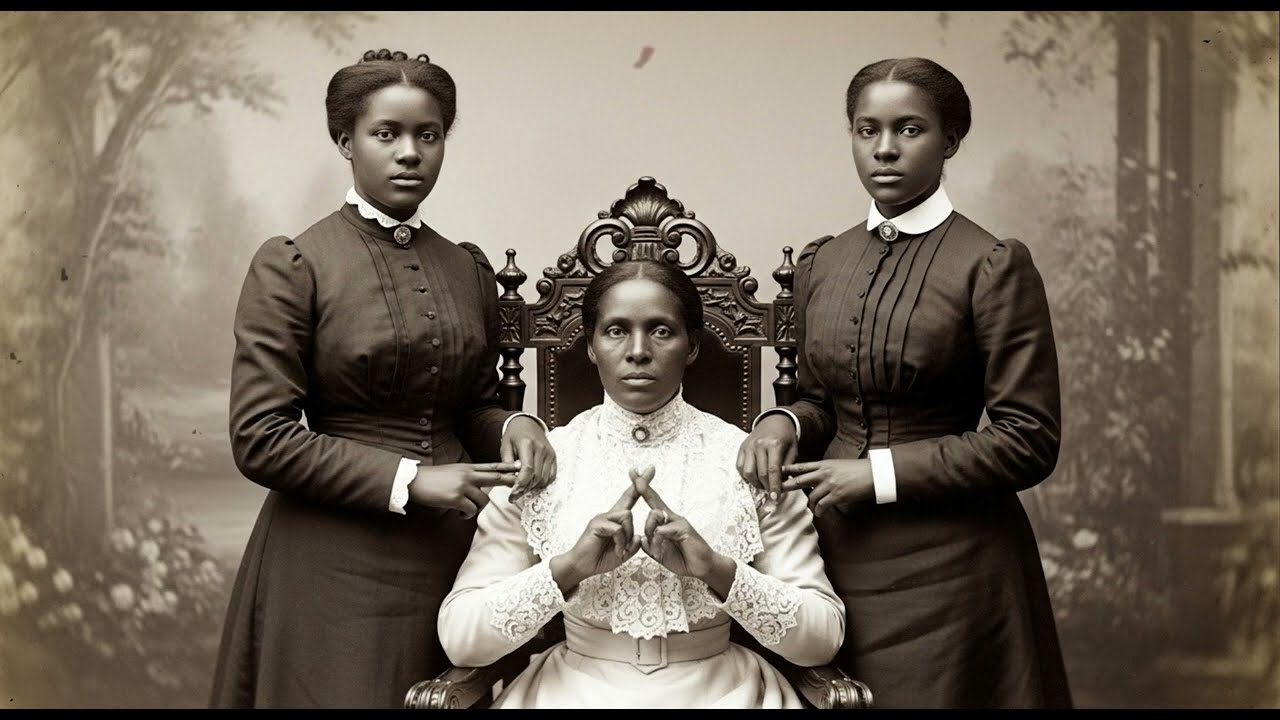

In a dimly lit archive room in New York City, surrounded by the smell of old paper and the quiet hum of preservation equipment, Dr. James Mitchell stumbled upon a secret that had been hiding in plain sight for over 130 years. It started with a donation box—an unassuming collection of glass plate negatives wrapped in yellowed newspaper from 1923, the kind of forgotten debris that often ends up in estate sales. Mitchell, a veteran archivist at the New York Historical Society, expected to find the usual suspects of the Victorian era: stoic merchants, stiff wedding parties, and solemn children in their Sunday best. But one image stopped him cold. It was a portrait of a mother and her two daughters, three African-American women dressed in the height of 1890s fashion, staring back at the camera with a quiet, regal dignity. At first glance, it was simply a beautiful family photo. But then, Mitchell looked closer. He looked at their hands. And in that moment, history began to rewrite itself.

The mother sat in the center, flanked by her daughters who stood protectively on either side. Their expressions were calm, their posture perfect. But their hands were doing something strange. The mother’s fingers were interlaced in a highly specific, unnatural pattern—right thumb crossed over left, index and middle fingers extended, the rest curled tight. The daughters, resting their hands on their mother’s shoulders, mirrored this odd geometry with variations of their own. Mitchell knew Victorian photography. He knew that subjects were told to keep still, to rest their hands naturally. These gestures were not natural. They were deliberate. They were purposeful. They were a code.

This discovery launched a detective story that would peel back the layers of post-Reconstruction America to reveal a hidden world of resistance, ingenuity, and survival. What Mitchell found wasn’t just a quirky family photo; it was the key to a sophisticated underground network that operated right under the noses of white authorities in 1890s New York. It was a system built by African-American families to protect themselves in a city that was actively trying to erase their rights, their property, and their identities.

The Mystery of Studio 247

Mitchell’s obsession with the hand signals led him to a tiny etching in the corner of the glass plate: “NY892247.” This alphanumeric breadcrumb trail led him to Studio 247 on 8th Avenue, operated by a photographer named Thomas Wright. On the surface, Wright was a white photographer from Massachusetts. But a deeper dive into his business records revealed something extraordinary for the time. While many studios in the 1890s either refused Black clients or charged them exorbitant “nuisance fees,” Wright’s advertisements ran in African-American newspapers. He welcomed everyone. But he didn’t just take their pictures; he became a silent partner in their survival.

Collaborating with historian Dr. Sarah Chen, Mitchell began to piece together a puzzle that had been scattered across court records, church basements, and forgotten legal files. They realized that the hand positions weren’t just artistic choices—they were data. In an era before digital databases, before reliable birth certificates or social security numbers for many marginalized people, this network had created a visual verification system.

The “Hand Code,” as it came to be known, was a brilliant solution to a devastating problem. After the collapse of Reconstruction in 1877, Black families in the North faced a bureaucratic nightmare. They weren’t fighting slavery anymore; they were fighting a system designed to strip them of their assets through paperwork. Without birth certificates or marriage licenses—documents many who fled the South didn’t have—they couldn’t prove they owned their homes, couldn’t inherit property, and couldn’t establish legal identities.

A Shadow Archive of Justice

Enter the network. Dr. Chen discovered a pattern in legal victories from the era involving a lawyer named Robert Hayes. Hayes won an unusual number of property disputes for Black families, and his secret weapon was often photographic evidence. But not just any photos—portraits taken by Thomas Wright, featuring the specific hand codes.

The theory that emerged was breathtaking in its scope. The network—comprising lawyers like Hayes, photographers like Wright, ministers, and community leaders—used these portraits to “tag” families. The mother’s hand position might signify her status as a head of household or a vetted member of the community. The daughters’ positions could indicate their legal standing or need for documentation. It was a shadow archive, a parallel system of identification created by the people, for the people. When the official courts said, “You have no proof of who you are,” Hayes could produce a dated, coded portrait that had been cataloged by the network, effectively proving the family’s existence and standing.

This revelation transforms our understanding of civil rights activism. We often think of resistance in terms of marches, protests, and speeches. But here was resistance in the form of a family portrait. Here was a revolution fought with lace gloves and glass negatives. It was quiet, it was dignified, and it was incredibly dangerous. If the wrong people had decoded the system, the network could have been dismantled, the families targeted. The fact that it remained a secret for over a century is a testament to the discipline and solidarity of those involved.

The Woman in the Chair

But who was the woman in the photograph? The investigation led Mitchell to Patricia Johnson, a 72-year-old Brooklyn resident and the great-granddaughter of the woman in the chair. Her name was Eleanor Morrison. Eleanor had been born enslaved in Virginia and had come North after the Civil War, building a life as a seamstress renowned for her intricate lacework.

Patricia revealed that while the specific “spy craft” of the network had been lost to oral history, the spirit of Eleanor’s work had survived. “She helped people,” Patricia told Mitchell. “She knew how to navigate every system.” Eleanor wasn’t just a passive subject in a photo; she was likely a node in the network, a connector who helped other families find housing, lawyers, and safety. The portrait was her badge of office.

In a poignant twist, Eleanor’s own diary, donated to the Historical Society, confirmed the theory. “Had our portrait made today,” she wrote. “Mr. Wright is a kind man, understands what we are building… I told the girls this picture will matter someday. People will see what we did here.” She knew. She looked into the lens of history and planted a flag.

Netizen Reactions: The Internet is Shook

As this story broke, social media platforms lit up with a mix of awe, emotion, and detective fever. The idea that a simple family photo could hold such deep, revolutionary secrets resonated with a generation obsessed with hidden details and lost history.

“I’m literally crying looking at my own family albums now,” one user commented on a viral thread about the discovery. “Imagine being so smart, so resilient, that you invent your own ID system right under the nose of a system that wants to erase you. Eleanor Morrison is a hero.”

“The way they hid it in plain sight is what gets me,” another user wrote. “To a racist official, it’s just a ‘nice picture.’ To the community, it’s a lifeline. It’s the ultimate code-switching. It’s brilliant and heartbreaking at the same time.”

True crime and mystery fans were equally captivated, but for once, the “twist” wasn’t a tragedy—it was a triumph. “I clicked because I thought it was going to be something creepy about the hands,” a Reddit user admitted. “I stayed for the history lesson. This is the kind of American history we don’t learn in school. It’s like a real-life National Treasure but with actual stakes.”

“The trust they must have had in that white photographer, Thomas Wright…” another comment mused. “In 1892? That’s a huge risk. He was a true ally before we even had a word for it. He used his privilege and his art to protect people. We need more Thomas Wrights.”

Many users also expressed a desire to see the full exhibition. “Put this in the Smithsonian immediately,” demanded one tweet that garnered thousands of likes. “Every single one of those portraits is a testament to survival. I want to see the other codes. I want to know what the different fingers meant!”

The Legacy of the Hands

The exhibition curated by Mitchell and Chen, featuring 20 of Wright’s coded portraits, became a pilgrimage site for descendants of the families involved. For people like Patricia Johnson, it was a moment of profound validation. Seeing her great-grandmother’s “quirky” hand pose recognized as a sophisticated tool of resistance gave new meaning to her family’s legacy.

The network eventually dissolved as the 20th century brought new challenges and new methods of activism, but for nearly a decade, it served as a shield for hundreds of families. It secured homes, protected inheritances, and kept families together.

This story forces us to look differently at the past. It reminds us that history isn’t just written by the victors; it’s also written in the quiet, subversive acts of everyday people refusing to be victims. It teaches us that resistance doesn’t always look like a fist in the air. Sometimes, it looks like a mother’s hand, resting gently on her lap, fingers crossed in a secret promise to the future.

What Do You See?

So, the next time you walk past an antique shop and see a bin of old, dusty photographs, or when you’re flipping through your own family albums, pause for a moment. Look closer. Look at the hands. Look at the positioning. Because as Eleanor Morrison proved, the simplest gestures can hold the most profound truths.

What do you think about this incredible discovery? Does your family have any stories of “hidden history” or secret ways they navigated the past? We want to hear from you. Drop a comment below, share this story, and let’s keep the memory of the “Hand Code” network alive. History is watching, and sometimes, it’s winking back at us.

News

VANISHED INTO THIN AIR: The Haunting Mystery of Angela Freeman and the Underwater Search That Uncovered Forgotten Secrets

The Silence of an Empty Driveway It is the kind of silence that screams. It’s the silence that greets you…

I’m 103… It Took Me 76 Years To Learn This (Don’t Waste Yours)

In a digital age obsessed with youth, filters, and the frantic chase for the next big thing, the most powerful…

THE FINAL CONFESSION: A Nurse Reveals the One Heartbreaking Regret That Haunts Almost Everyone Before They Go

There is a specific kind of silence that falls over a room when the end is near. It is not…

THE GIRL IN THE DARK: How a Vanished Student Returned From the Void with Snow-White Hair and a Vow of Silence

It is the kind of story that nightmares are made of, a tale that whispers to the deepest, most primal…

MIRACLE IN KENTUCKY: The Girl Who Came Back From the Void—How Michelle Newton Defied the Odds After 42 Years

Imagine a silence that lasts for forty-two years. It is a silence that swallows birthdays, holidays, and milestones, leaving behind…

THE 3-PAGE CLUE THAT CHANGES EVERYTHING: Did AI Just Solve the JonBenét Mystery?

It was the morning after Christmas in 1996, a day that should have been filled with the joy of new…

End of content

No more pages to load