The 24-hour laundromat on the corner of 3rd and Main isn’t a place for lingering. It’s a place of transition, a sterile, fluorescent-lit box where people go to perform a chore and leave. The air smells of bleach and ozone. The rhythmic slosh of the washers and the warm hum of the dryers are the only sounds that break the late-night silence. It is a place of utility, not comfort.

So when the calls started coming into the Sheriff’s department about a “suspicious” person, they were all the more unsettling. The person in question wasn’t a vagrant, or a dealer, or anyone the night shift usually dealt with.

It was a little girl.

For two weeks, residents and late-night workers had seen her. A small, Black girl, maybe ten years old, would arrive every night around 8:00 PM. She would stay for two or three hours, always alone, always in the same corner booth under the brightest light, and then disappear.

To Sheriff Mark Brody, a 30-year veteran of the force, the call sounded like a tragedy in the making. A child, alone, at night? It was a parent’s worst nightmare. He’d seen too much in his career to expect a happy ending. He rolled his cruiser to a stop across the street, the laundromat’s bright, clean interior looking like a fishbowl in the dark.

And there she was. Just as the caller had said. A small, solitary figure, her back to the door, hunched over a book.

Sheriff Brody pushed the door open, the bell over it jangling loudly, making her jump. She looked up, her eyes wide with a fear that was quickly masked by a practiced, defiant glare.

“Evening, ma’am,” Brody said, his voice gentle, trying to disarm her. “A little late for homework, isn’t it?”

The girl, who he would come to know as Tiana, simply shrugged. “Just doing my laundry.” She motioned to a single, whirring dryer.

Brody looked at the dryer, then at her. He was a cop, but he was also a father. His instincts were firing on two different levels. The cop in him saw the lie. The dryer was running, yes, but through the small glass window, he could see just one or two items tumbling inside: what looked like a child’s school uniform.

“That’s a small load,” he said, moving closer. He saw her notebook on the plastic table. It was filled with neat, precise cursive. On top of it was a sixth-grade science textbook. “What are you studying?”

“Photosynthesis,” she said, her voice small but proud. “We have a test on Friday.”

“Tiana,” he said, reading the name off the top of her paper. “That’s a nice name. I’m Sheriff Brody. Where’s your mom? Does she know you’re here?”

The girl’s composure cracked, just for a second. “She’s at work. She knows. It’s fine.”

But Brody knew it wasn’t fine. He sat down in the plastic booth opposite her. “I’m not here to get you in trouble, Tiana. I’m here to make sure you’re safe. But you and I both know there’s something else going on. Why are you really here every night?”

Tiana’s eyes darted to the door, then to the floor. She had been taught to be wary, to never show weakness. Her mother, Janelle, worked two jobs—one as a nurse’s aide at a nursing home and another cleaning offices—and her one standing rule was to “never be a burden.”

For the past three weeks, their apartment had been a cold, dark, and silent place. A miscommunication with the power company after a missed payment had plunged their small home into darkness. Janelle was frantic, working extra shifts, spending her breaks on the phone trying to get it restored, all while putting on a brave face for her daughter.

But Tiana knew. She saw the stress in her mother’s eyes, heard the hushed, desperate phone calls. And she saw her own grades beginning to slip. How could you study in the dark? How could you focus when you were shivering under three blankets?

So Tiana had formed a plan. She hoarded the lunch money her mother left her, trading hot meals for apples. It was just enough. Two dollars in quarters. Enough to run a single dryer for over an hour. It wasn’t about the laundry; the single uniform she washed by hand in the sink was just an excuse.

It was about the light. And it was about the warmth.

The laundromat was the only place in her world that offered both, for the price of a few quarters. It was her sanctuary, her study hall, her secret. She would do her homework, and then, in the last ten minutes, put her uniform in the dryer so it would be warm when she put it on for school the next morning.

She looked at this large police officer, a man who represented authority, a man who could take her away, and the secret she had held so tightly finally spilled out.

“The power’s off,” she whispered, the tears she had been fighting finally welling in her eyes. “My mom… she’s trying, she’s trying so hard, but it’s been three weeks. I have this test, and I can’t fail. I just… I needed a light.”

She confessed it all. The lunch money. The cold. The fear of telling her mom and making her feel worse.

Sheriff Brody sat there, stunned into silence. He had come expecting to find a runaway, a delinquent, maybe a victim of a broken home. He had not expected to find this. He was looking at a 10-year-old child who was so determined to get an education that she had built a study carrel out of a laundromat, using the warmth from a dryer as her fireplace.

He was a 30-year veteran. He had seen the worst of humanity. But this quiet, heartbreaking dignity, this child’s desperate, resilient fight for normalcy, was something he was unprepared for.

He looked at her neat homework, her worn-out textbook, and the single, tumbling school uniform. He felt a profound, unfamiliar tightness in his chest. And to his own complete and total surprise, Sheriff Mark Brody, a man who hadn’t cried in front of another person in a decade, felt his eyes burn. He wiped a tear from his face, turning his head away, embarrassed.

“It’s okay, kid,” he said, his voice thick. “You’re not in trouble. You’re going to be okay.”

The tears weren’t just for Tiana. They were for the whole, broken, unfairness of it. They were for her mother, who was working herself to the bone and still couldn’t keep the lights on. They were for a system where a 10-year-old had to choose between lunch and a light to study by.

But Brody was a man of action, not just emotion. “Come on,” he said, standing up. “Pack your books. Let’s get you home.”

He drove her to the dark apartment complex. He walked her to the door. As if on cue, Janelle’s car pulled up. She saw the police cruiser and her daughter, and her face went ashen with terror. She ran, thinking the worst.

“What’s wrong? Tiana? Are you hurt? What happened?”

Before Tiana could speak, Sheriff Brody held up a hand. “Ma’am, your daughter is perfectly safe. She’s, in fact, one of the most incredible kids I’ve ever met.”

In the dim glow of the security lights, he explained. He told Janelle where he’d found Tiana. He told her why. And as he spoke, Janelle’s face crumpled. The strong, proud mask she wore for the world dissolved. She wasn’t a failure; she was a mother whose daughter was trying to protect her. The two of them embraced, sobbing.

Brody went back to his car, but he didn’t go back on patrol. He made a call to his sergeant, telling him he was “off the board” for an hour. He drove to an all-night diner, bought two bags of hot food, and drove back, handing them to Janelle. “You two eat,” he said. “I’ll be back.”

He wasn’t. But at 7:00 AM the next morning, an electrician from the power company arrived. He had a work order, he said, for an “emergency reconnect.” The bill, he explained, had been “handled.”

At 8:00 AM, two of Brody’s deputies, who were “just in the neighborhood,” knocked on the door with two large boxes of groceries, claiming the local pantry had an “excess” they needed to get rid of.

Sheriff Brody had told his deputies Tiana’s story, and it had ripped through the department. The “why” was so powerful, so raw, that it had sparked a quiet, ferocious need to fix it. The deputies had pooled their own money, paid the $350 power bill, and organized a grocery run, all before their shift had even started.

The story eventually leaked, as all good stories do. The local paper picked it up. People in the town, who had once called to report a “suspicious” girl, now called to ask how they could help. A fund was set up. Tiana and Janelle were no longer invisible.

Tiana got an ‘A’ on her science test. She never went back to the laundromat at night. She didn’t need to. She had her own light, in her own room. And she had a town that, thanks to one Sheriff’s tears, had finally opened its eyes.

News

VANISHED INTO THIN AIR: The Haunting Mystery of Angela Freeman and the Underwater Search That Uncovered Forgotten Secrets

The Silence of an Empty Driveway It is the kind of silence that screams. It’s the silence that greets you…

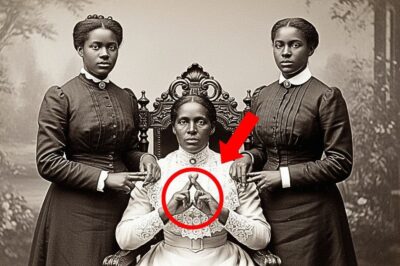

It was just a portrait of a mother and her daughters — but look more closely at their hands.

In a dimly lit archive room in New York City, surrounded by the smell of old paper and the quiet…

I’m 103… It Took Me 76 Years To Learn This (Don’t Waste Yours)

In a digital age obsessed with youth, filters, and the frantic chase for the next big thing, the most powerful…

THE FINAL CONFESSION: A Nurse Reveals the One Heartbreaking Regret That Haunts Almost Everyone Before They Go

There is a specific kind of silence that falls over a room when the end is near. It is not…

THE GIRL IN THE DARK: How a Vanished Student Returned From the Void with Snow-White Hair and a Vow of Silence

It is the kind of story that nightmares are made of, a tale that whispers to the deepest, most primal…

MIRACLE IN KENTUCKY: The Girl Who Came Back From the Void—How Michelle Newton Defied the Odds After 42 Years

Imagine a silence that lasts for forty-two years. It is a silence that swallows birthdays, holidays, and milestones, leaving behind…

End of content

No more pages to load