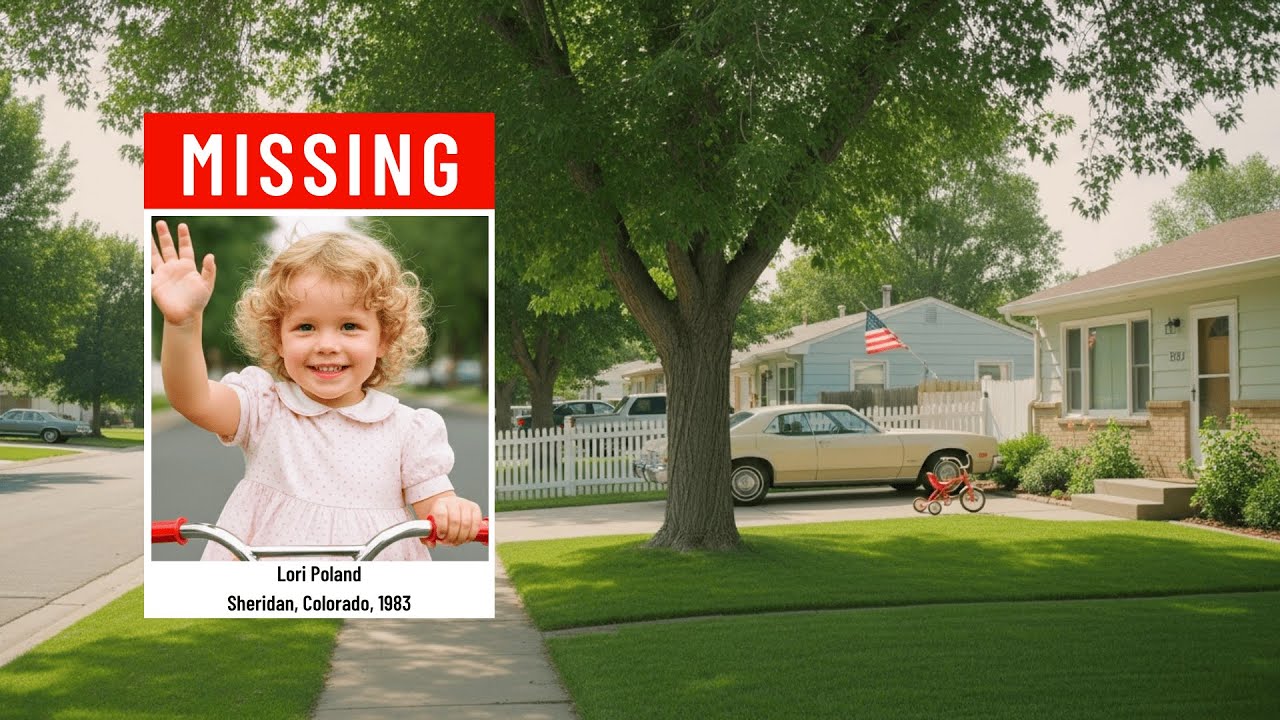

On a warm August afternoon in 1983, the town of Sheridan, Colorado, felt like the safest place on earth. It was a time when summer days stretched endlessly, lawns were manicured, and the sound of sprinklers was the only disturbance. In front of a modest brick house on West Oxford Avenue, three-year-old Lori Poland sat on the front step with her brother, their fingers sticky from popsicles. Her father, watching from the porch, smiled at the scene before stepping inside for just a moment to grab a treat for himself. He left the door cracked open, a casual act of trust in a safe neighborhood. But when he returned less than two minutes later, the silence was deafening. His son was standing by the curb, staring down the empty street. Lori’s plastic tricycle lay tipped on its side, one wheel spinning lazily in the breeze. Lori was gone.

The panic that followed was immediate and primal. Her father ran to the corner, shouting her name, his voice echoing off the quiet houses. Neighbors poured out, searching backyards and alleys, but it was as if the little girl had evaporated. Police arrived within minutes, swarming the block. They asked every resident the same questions: Did you see a car? Did you hear anything? But answers were scarce. A few people mentioned a vehicle slowing down, but details were blurry. As the sun set, the search expanded into a desperate grid of volunteers and officers moving shoulder-to-shoulder through fields and parks. Search dogs picked up a scent only to lose it yards away at the curb, confirming the terrifying reality that Lori had been taken by a vehicle.

For three agonizing days, the Poland family lived in a suspended state of nightmare. The search radius widened to neighboring counties, and Lori’s preschool photo—her shy smile and honey-blonde curls—was plastered on every telephone pole. The community held vigils, candles flickering against the rain that had begun to fall, washing away potential evidence. By the fourth day, hope was a fragile thing. The active ground search was scaling back. The word “survival” was being whispered with doubt. But forty miles away, deep in the mountains west of Denver, a miracle was waiting to be found.

A couple hiking along an old service road stopped near a dilapidated, wooden outhouse—a relic left behind by hunters decades earlier. The husband, a bird watcher, stepped closer and froze. He heard a sound. It was faint, barely more than a breath, but it was unmistakably human. “Help me,” a tiny voice whispered from the ground. Terrified, the couple shone a flashlight into the black pit beneath the structure. Fifteen feet down, amidst the filth and darkness, a pair of eyes looked back. It was Lori.

Rescuers arrived in a swarm of sirens and disbelief. A firefighter was lowered into the pit and emerged holding a small, trembling body wrapped in a dirty towel. Lori was barely conscious, suffering from hypothermia, dehydration, and chemical burns, but she was alive. She had survived four days in absolute darkness by standing on a mound of debris to keep her head above the waste. When a nurse at the hospital later tried to reassure her that she was safe, Lori whispered a sentence that broke the hearts of everyone in the room: “I live here now.” It was the heartbreaking logic of a child trying to make sense of the unthinkable.

The investigation that followed was swift and intense. Lori, though traumatized, provided key details: a man, an orange car, and a promise of candy. Detectives scoured DMV records for orange Datsun sedans in the area and zeroed in on Robert Paul Thiret, a 21-year-old living just miles from the Poland home. When police inspected his car, they found the smoking gun: blonde hairs matching Lori’s, fibers from her pink dress, and a candy wrapper identical to the ones her father had bought. The physical evidence was overwhelming, placing Lori inside his vehicle.

However, the road to justice was paved with frustration. Thiret denied everything, claiming he had only tried to help a lost child. Despite the DNA and fiber evidence, his defense team argued circumstantial doubt and utilized a false alibi provided by his wife. To spare Lori the trauma of testifying again and risking a hung jury, prosecutors accepted a plea deal. Thiret was sentenced to 10 years but served only six. The light sentence sparked public outrage and protests, with signs reading “6 Years for a Child’s Life.” The community felt betrayed, but for Lori, prison walls were never going to be the true measure of justice.

Lori’s story didn’t end with the trial. The trauma of those four days in the dark followed her for years—nightmares of the pit, a fear of the dark, and the heavy burden of being the “miracle girl.” But as she grew older, Lori made a choice. She refused to let the man who took her childhood define her adulthood. She studied psychology, eventually becoming a therapist specializing in childhood trauma. She co-founded the National Foundation to End Child Abuse and Neglect (EndCAN), turning her pain into a platform to help others.

In her memoir, fittingly titled I Live Here Now, Lori reclaimed the words she once whispered in fear. She transformed them into a declaration of presence and resilience. She teaches survivors that healing isn’t about erasing the past, but learning to live beside it. “The man who hurt me thought he buried me,” she famously said. “He didn’t know I was a seed.” Today, Lori Poland stands as a powerful testament to the human spirit, proving that even from the deepest darkness, light can emerge.

News

The 41-Minute Mystery: Why The Official Narrative on the Nancy Guthrie Case Just Shattered

The news broke on a quiet Saturday morning in Tucson, creating shockwaves that rippled all the way to the NBC…

Heartbreak in Port Charles: The Shocking Truth Behind Jane Elliot’s Final Exit and Why General Hospital Will Never Be the Same

The news hit the internet with the force of a tidal wave, leaving daytime drama fans across the nation absolutely…

General Hospital Shocker: Is This The End of The Road for Emma Scorpio-Drake? The Heartbreaking Twist That Has Fans Reeling

The air in Port Charles has been thick with tension lately, but nothing could have prepared General Hospital fans for…

General Hospital Stunner: The Queen of Fashion Wakes Up With the Perfect Clapback While Baby Daddy Drama Explodes in Port Charles

It is the moment every single General Hospital fan has been waiting for with bated breath, counting down the days…

he Billionaire’s Breeding Experiment: Inside the Desert Ranch Where Science Went Dark

It is the year 2006 in St. Thomas, and the room is filled with some of the most brilliant minds…

The Unthinkable Nightmare: Inside the Terrifying Disappearance of Savannah Guthrie’s Mother and the High-Stakes Federal Hunt for Answers

It happened in the blink of an eye, shattering the peace of a quiet Arizona evening and plunging one of…

End of content

No more pages to load